2024-4-20 06:20 /

日本漫画简史

——「森实」的复活之日

原作者:巽孝之 | 英译:克里斯托佛·博尔顿(Christopher Bolton)

文章原名:Mori Minoru's Day of Resurrection

中译:FISHERMAN

原文链接(JSTOR)

随着日本科幻步入新千年暨21世纪,日本科幻迷所期待的,或许是沉寂已久的“远古神作(家)”的复苏。然而,没有人预见到森实(モリ·ミノル)会再次现身。

森实,是一位曾在五十年前发表过作品的幻之漫画家。他是一系列昙花一现但影响深远的漫画作品背后的灵魂人物,但令人费解的是,它们却在五十年代突然停止了出版。近年来,小学馆终于出版了这位艺术家的漫画全集复刻版,在当时,这些作品得到了其他漫画家同行和初露头角的手冢治虫的认可。因《宇宙战舰大和号》和《银河铁道999》等漫画闻名海内外的松本零士,将森实、手冢治虫和田川纪久雄列为五十年代最伟大的三位漫画家。

尽管广受好评,有一天,这位自称森实的男人停止了出版,并几乎消失得无影无踪。直到十年后,他才再次浮出水面,只不过这次,是作为小说家。1961年,他向早川书房旗下的《科-幻杂志》(S-Fマガジン)主办的科幻小说竞赛投稿了一篇小说,并凭借这部名为《给大地以和平》(地には平和を)的作品获得了“努力赏”。1962年,他用另一个笔名在同本杂志上发表了作品《易仙逃里記》(英译名为Memoirs of an Eccentric Time Traveler)。1963年,他的《给大地以和平》与《茶泡饭的味道》(お茶漬けの味)获得了第50届直木赏(日本最著名的通俗小说新人赏)的提名。这宣告了漫画家森实的“死”,同时也标志了第一代日本科幻的诞生,而后者的代表人物,正是森实的中之人、初代日本SF大手子中的一员——小松左京。在接下来的日子里,小松左京将为日本“通俗科幻”小说流派的形成贡献力量,而他的小说《日本沉没》则助长了这种流派向西方的输出传播。《日本沉没》是小松左京的代表作:它被翻译成了英语、西班牙语、俄语和其他几种西方语言。

使小松左京早期创作的漫画在几年前重见天日的,是(小松)在漫画书店MANDARAKE的货架上发现的森实漫画珍本《大地底海》(1950-1952年间连载)。这促使小松左京搜索自己的档案,并在档案中发掘出了许多他在学生时代创作的漫画手稿。2001年秋,得知这一(再)发现的消息后,小学馆的编辑们赶忙再版了这些作品,并于2002年初结集出版了四卷合一的《森实,a.k.a.小松左京的幻之漫画全集》(幻の小松左京=モリ·ミノル漫画全集)。彼时,小松刚满七十岁,正是放出早期作品(retrospective publication)的好时机...很难想象会有比森实的漫画更合适的作品了。[1]

小松左京,本名小松实,1931年出生于大阪。他就读于京都大学,在1954年毕业时,他取得了意大利文学的学士学位,并养成了对前卫艺术的浓厚兴趣:小松实的毕业论文研究的是意大利作家路伊吉·皮兰德娄,同时,他也是战后日本先锋派(原文为experimental)作家花田清辉和安部公房的狂热粉丝。战后的几年间,日本大部分地区的经济形势仍不容乐观。在这样的环境下,身为贫困生的小松实选择靠漫画来赚钱。1949年,受手冢治虫作品启发的小松实开始以笔名“森实”创作漫画。他发现,比起散文手稿,漫画要更容易卖出:出版商买下了他的全部作品,随后,他很快便赚到了第一桶金。大学毕业后,小松实从事过其他杂七杂八的工作——工厂经理、漫才电台作家、财经杂志《アトム》的通讯员——直到他作为科幻小说作家“小松左京”出道为止。

1964年,小松左京的小说《日本阿帕契族》(日本アパッチ族)销量超过了五万本。同年,他发表了小说《复活之日》(復活の日);1980年,深作欣二(电影《大逃杀》的监督)将这部小说搬上了银幕。1966年,小松左京创作了小说《无尽长河的尽头》(果しなき流れの果に),时至今日,它仍经常排在各种“日本有史以来最棒的科幻小说”排行榜的榜首。然后1973年,小松左京出版了《日本沉没》;这本书描绘了一系列使日本列岛沉没的地震事件。预见了汤姆·克兰西现实模拟风格的《日本沉没》狂售四百万册,并于1973年被改编成了真人电影和漫画(森实:什么...在想我的事情?),广受人们喜爱;其英文删节版首次出版于1976年。《日本沉没》的热度至今丝毫未减:2006年,才华横溢的年轻监督樋口真嗣对1973年的电影做了精美而激进的翻拍。

在赢得多项由日本科幻爱好者颁发的SF奖项后...1980年,小松左京在担任日本科幻作家俱乐部(日本SF作家クラブ/SFWJ,官网:http://www.sfwj.or.jp)第三届主席的同时,帮助设立了日本SF大奖。2000年,角川春树出版社以他的名字设立了一项文学奖。直至本文截稿时,小松左京(1931-2011,R.I.P)仍活跃在创作第一线:他正在写《虚无回廊》,并称之为他的毕生心血。

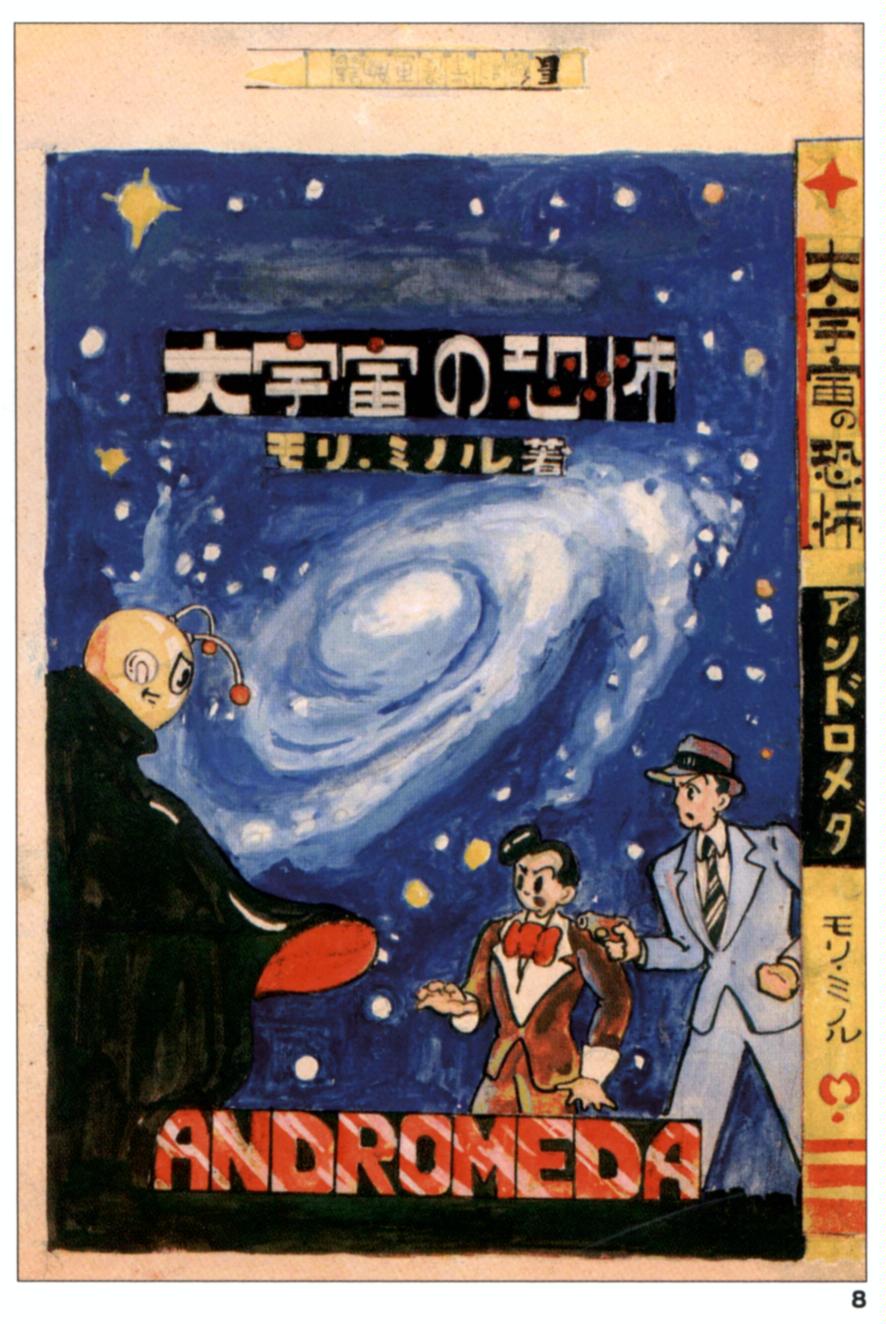

结合小松左京的文学历程,重读森实的漫画,我们将看到一种近乎可怕的连续性:映在我们眼前的,是这位天才横跨半世纪的创作生涯。小松左京学生时期的左翼倾向,解释了为什么森实会选择将列夫·托尔斯泰的杰作《傻子伊凡》改编成漫画《イワンの馬鹿》(1950年出版)。今天,我们可以发现森实的《仙女座:宇宙的恐怖存在》(大宇宙の恐怖アンドロメダ,上世纪五十年代出版)等漫画与伊万·叶菲列莫夫(Ива́н Ефре́мов)的小说《仙女座星云》(Туманность Андромеды)之间的关联。毕竟,促使小松左京提出自己的科幻创作理念的,正是他对这位俄罗斯科幻作家的崇拜。

不过,在这些漫画作品中,最引人注目的还是《大地底海》,毕竟,正是它使“森实”再次浮出水面。这部深受读者喜爱的作品曾三次移刊:1950年负责其出版业务的是不二書房,1951年改为白鳥舎,而1952年则变成了立东舍...随着每一次改版,作品的设定都发生了改变。故事源于一个大胆的幻想:世界四大沙漠——戈壁沙漠、撒哈拉沙漠、阿拉伯沙漠、以及伊朗的大盐湖沙漠——被一片广阔的地下海洋连接在一起,而这片大海则是一个名为“恶魔”的变异鱼人部落栖居的家园。漫画情节围绕着“地壳变动仪”展开,它所利用的特斯拉线圈技术可以移动地壳,并有着灭绝这片地下水源的潜能。从本作的出发点来看,它和《日本沉没》的世界观大同小异,在后者中,地质变化淹没了日本,并使日本民众像犹太人一样颠沛流离。

1995年,毁灭性的神户地震冲击了小松左京所在的关西地区。同年,奥姆真理教策划了东京地铁沙林毒气袭击,而它赞助创作的超自然传教漫画在这场恐袭后成了大家众矢之的。在袭击过后,有传言称,教团的科学部门曾经研究过特斯拉线圈,因为他们想要建造自己的地震武器。1950年出版的《大地底海》将故事设定在五十年后的未来,不幸的是,还没满五十年,它所设想的便在世纪末的95年成为了现实。

图片欣赏:

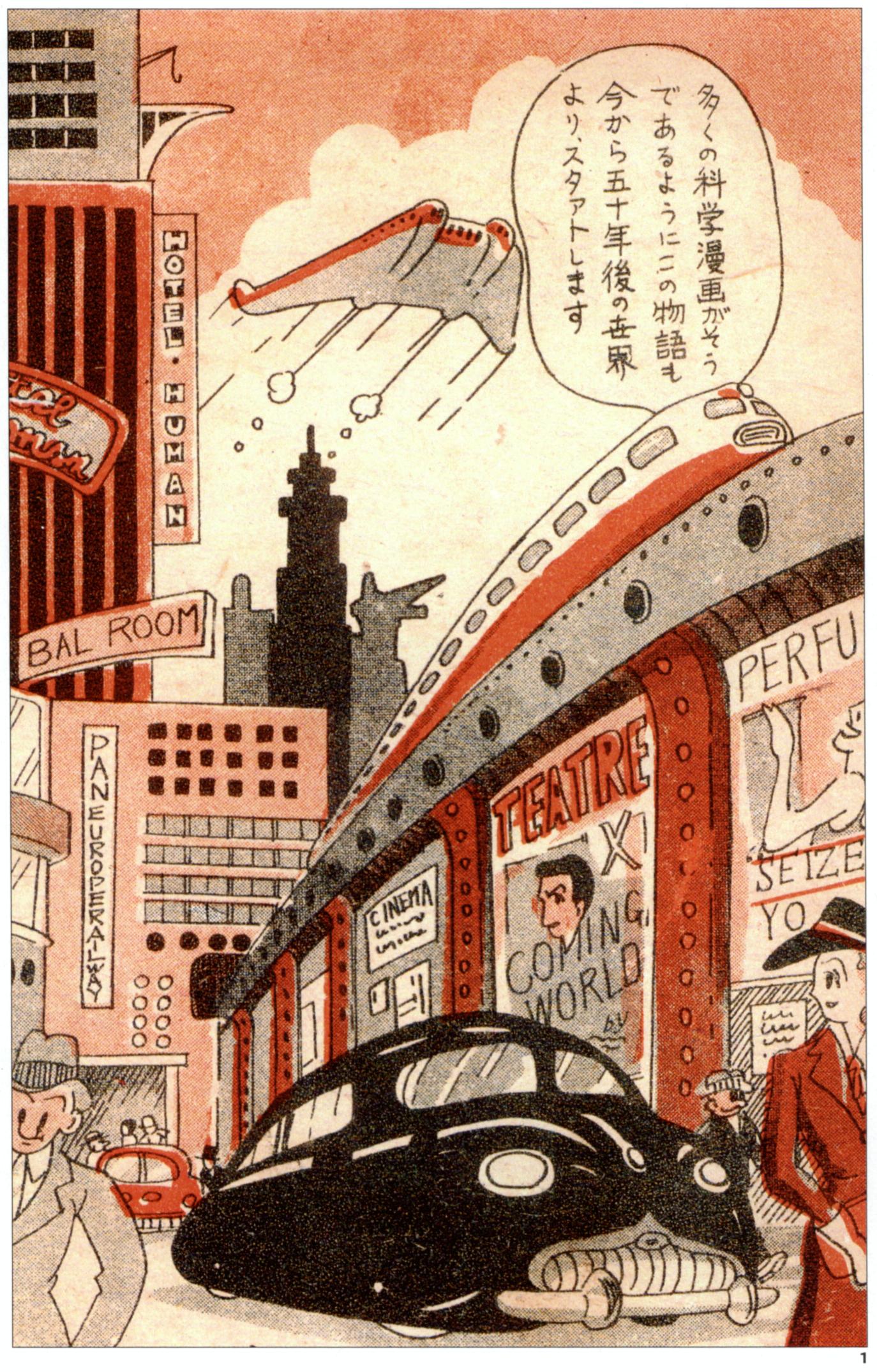

图1.《大地底海》的第一页。街景上方的对话框中写道:“这则故事,和许多其他科幻漫画一样,设定在五十年后的未来...”本文中出现的所有图片由小松左京本人提供。

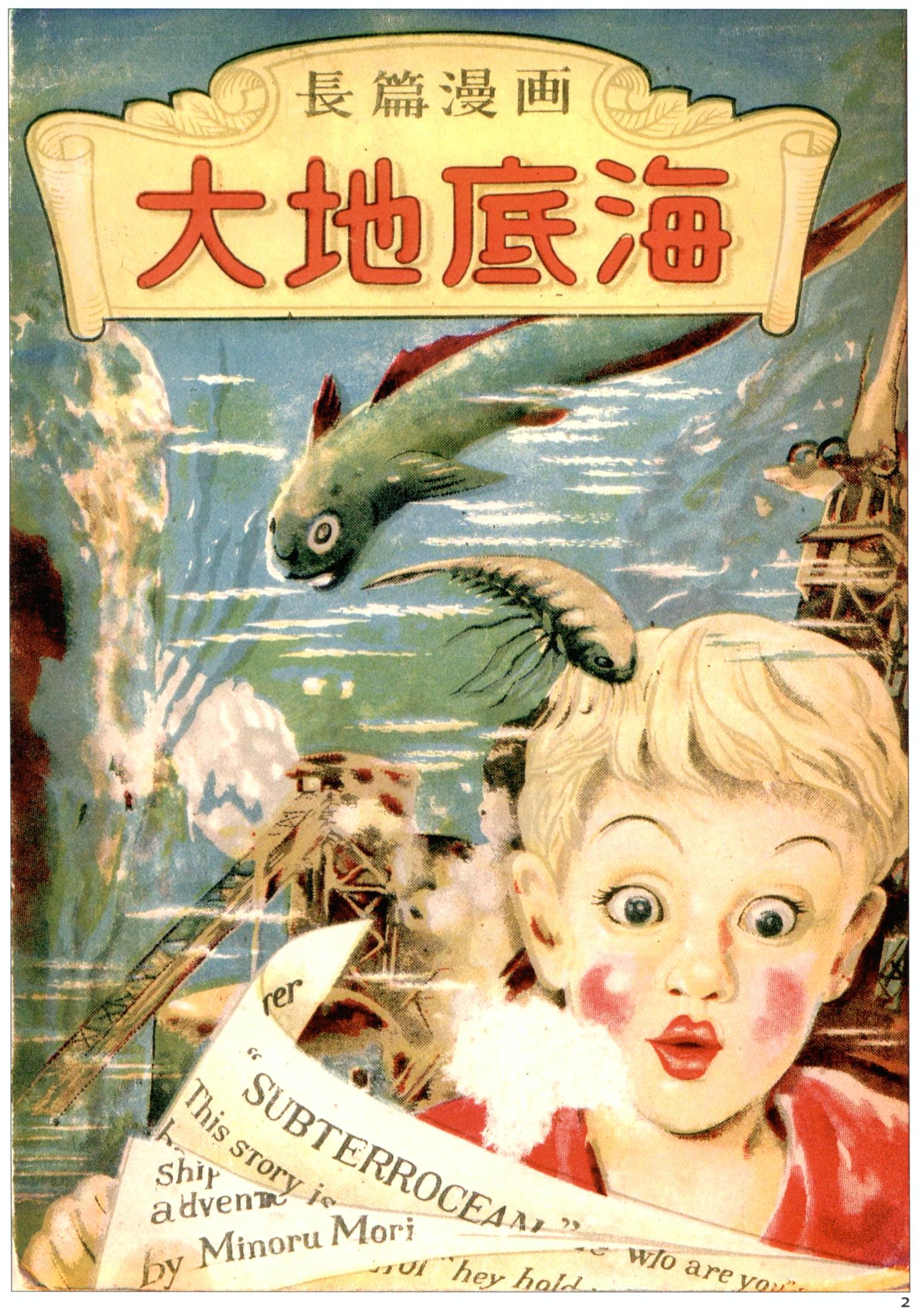

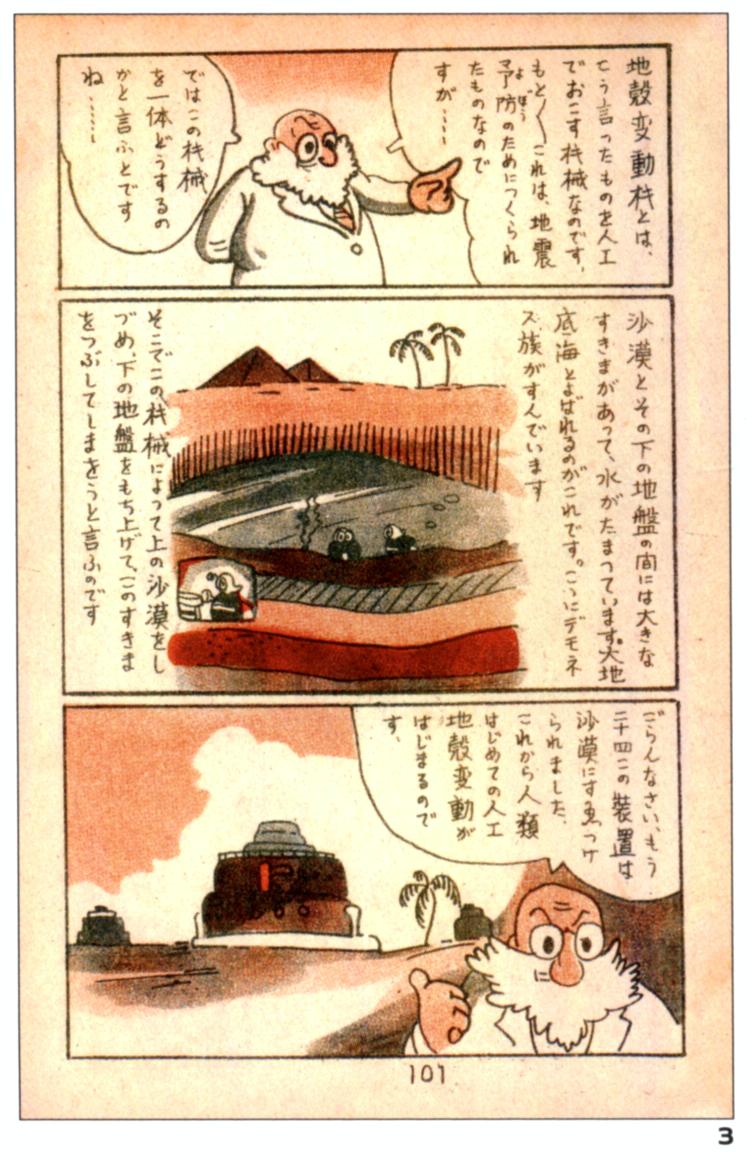

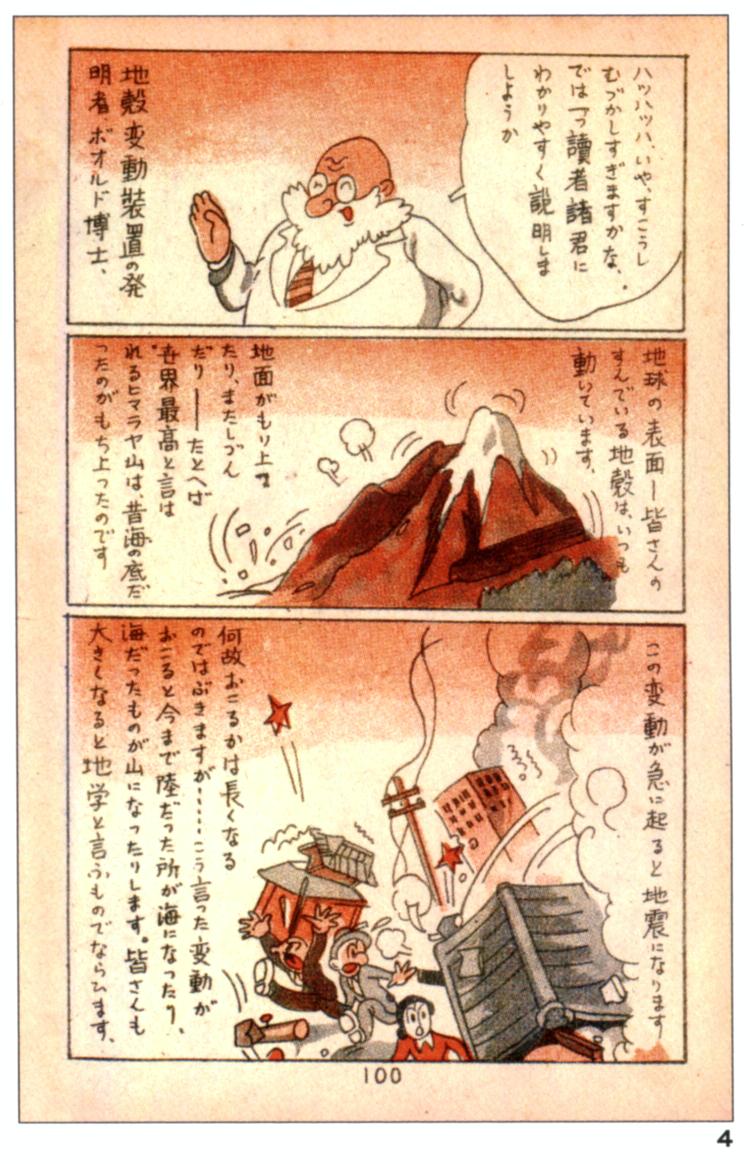

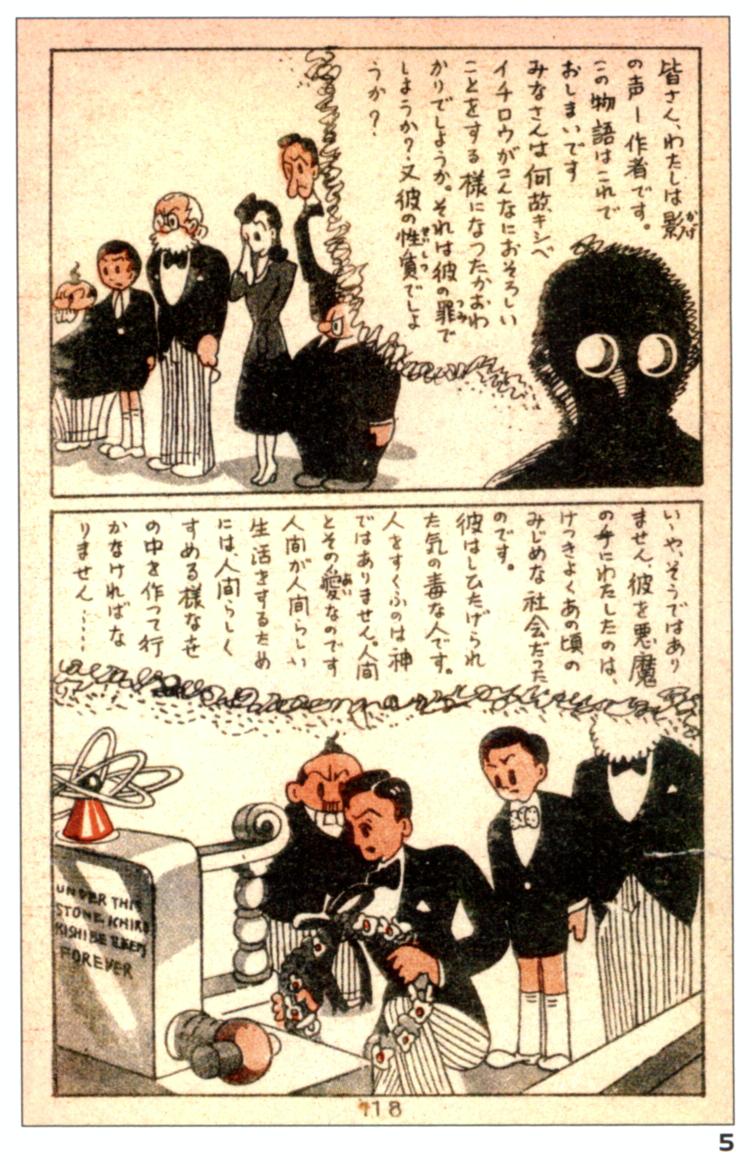

图2, 3, 4, 5.《大地底海》的封面和其中三页漫画。在图3上方的画格中,布尔多博士解释了他那可以控制地壳运动的“地壳变动仪”。这些机器原本是为了预防地震而设计的,但后来,它们却被安装在了世界最大的几个沙漠中,成为了某项精心设计的实验的一部分,其目的是(通过地震)压低地表、抬高岩层,并借此消除这些沙漠地底蕴藏的巨量水源。然而,这片大地底海却是名为“恶魔”的鱼人部落栖息的地方...

在图5的画格中,一位面色漆黑的角色作了自我介绍。他自称“影子的声音——作者”,并告诉读者,故事已经结束。“你明白为什么岸边一郎会做出如此可怕的事情吗?”它问道。“是因为他的罪孽?还是他的本性?不不。使他落入恶魔之手的,是这个时代所孕育的悲惨社会。他只是受压迫的穷苦大众中的一员罢了。而又有什么能够拯救像他这样的人呢?能带来救赎的绝不是神,而是其他人和他们的爱。若我们要作为人类而活,那我们就必须建立一个更加人道的世界。”

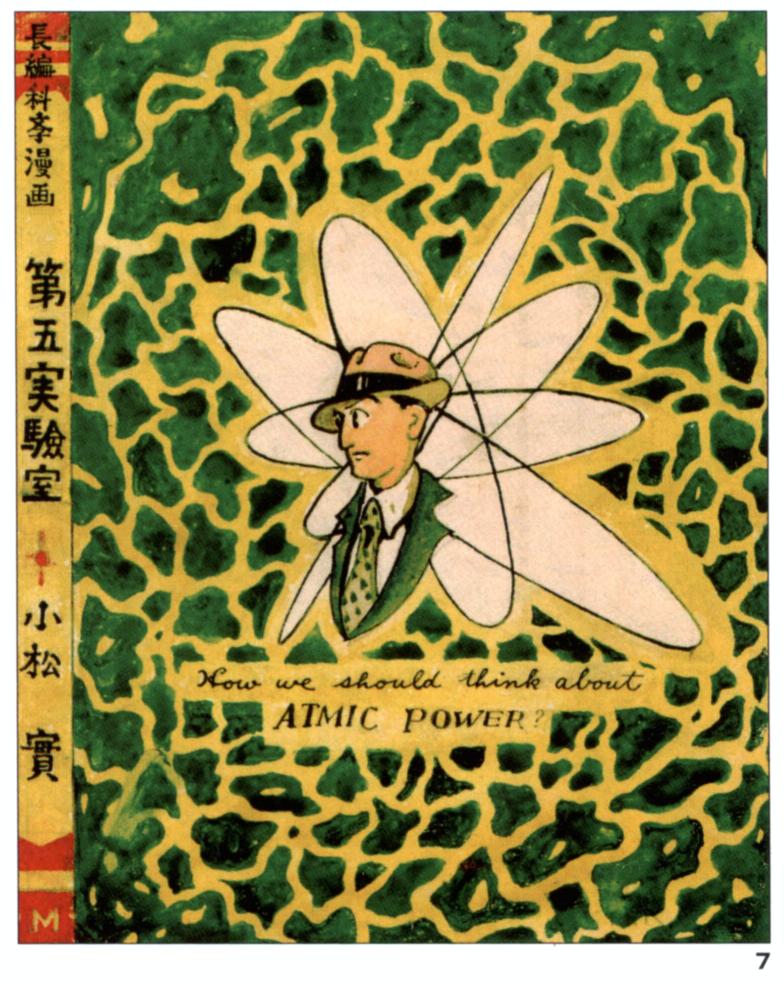

图6, 7. 漫画《第五实验室》的封面与封底,该作品于上世纪五十年代出版。

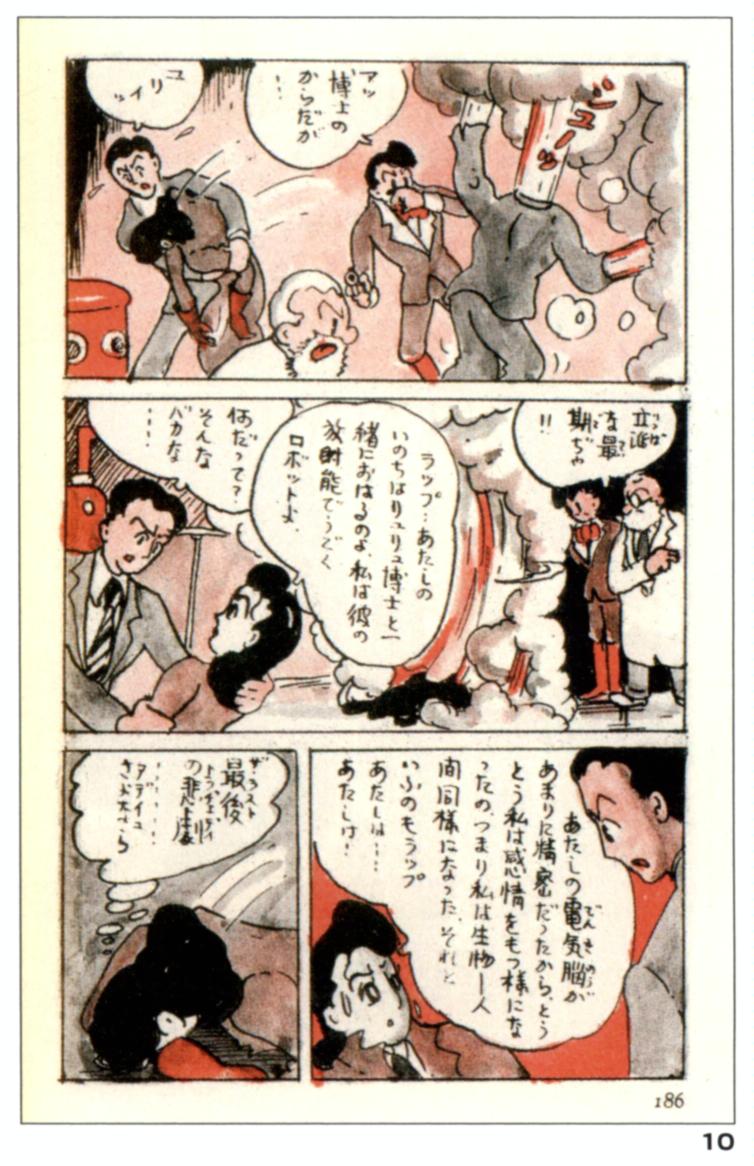

图8, 9, 10. 《仙女座:宇宙的恐怖存在》的封面和其中两页漫画。在图10中,反派角色龙龙(Ryuryu)博士的自爆使女主角尤莉(Yurii)不幸身亡。我们得知,尤莉是博士制造出来的机器人。“我是一个被他的思想控制的机器人。”她向男主坦白道,“我的电子脑被设计得如此精巧,以至于我开始有了感情。换句话说,我开始活着——就像人类一样。”

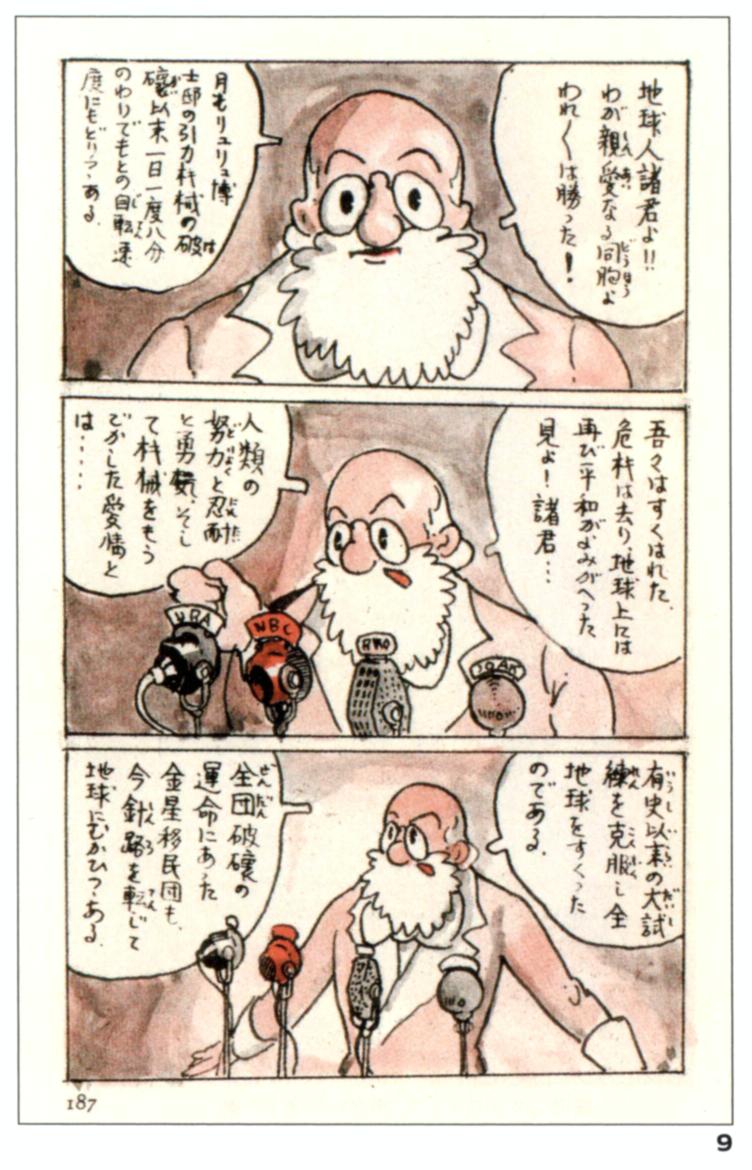

在图10中,白发苍苍的发言人宣布:龙龙博士的重力装置已被摧毁、地球脱离了危机。“我们得救了,”发言人说道,“危机已经消除,和平重返地球。女士们先生们,你们看,面对前所未有的挑战,人类的耐心、努力和勇气战胜了一切,而这场胜利的背后,是爱...它甚至鼓动了一颗机械做的心。”

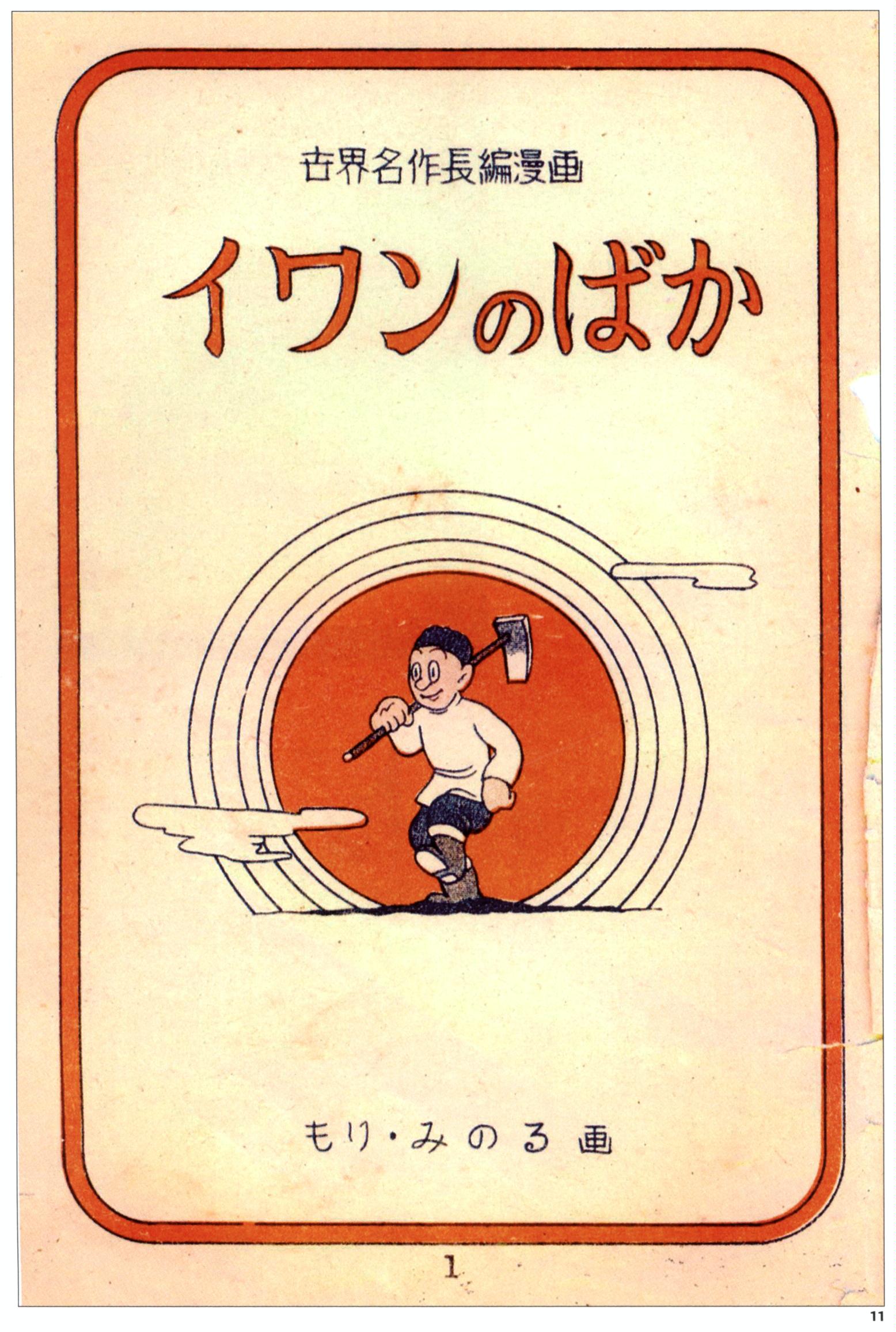

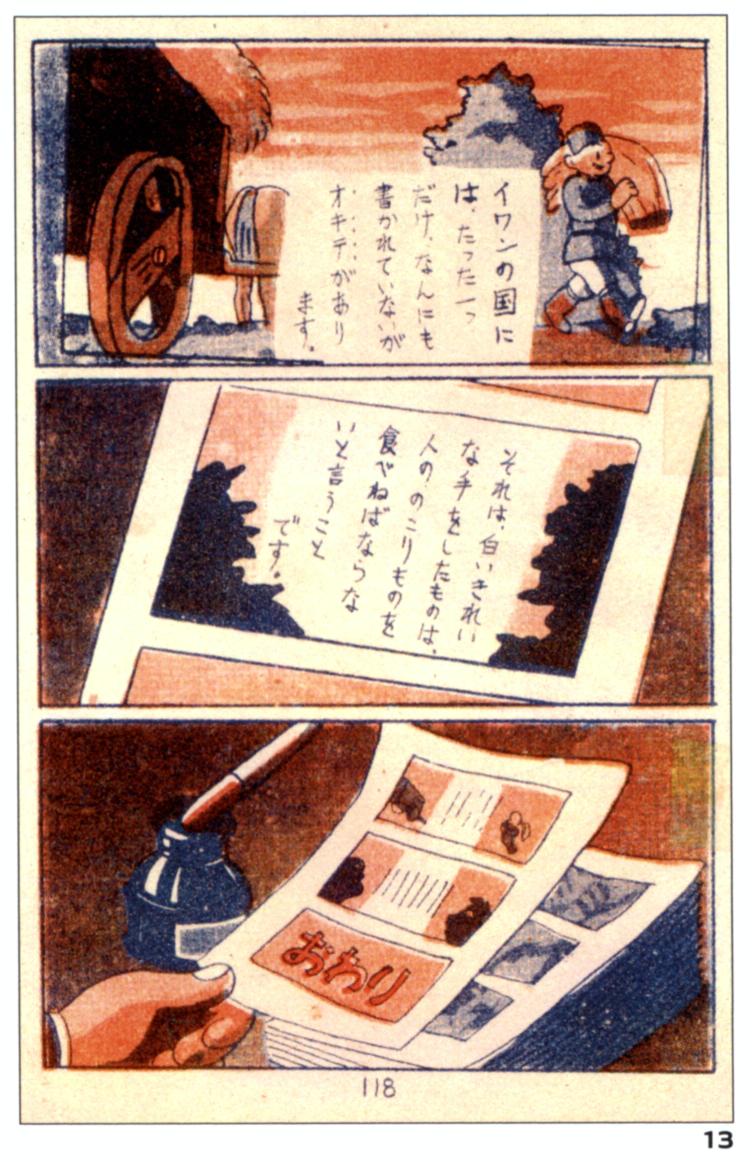

图11, 12, 13. 改编自托尔斯泰短篇小说的漫画《傻子伊凡》的封面、开场与结尾。漫画伊始,主角/读者站在恶魔的宫殿入口处;这里,是将要诱惑伊凡和他的哥哥们的魔鬼的寓所。“这些大门背后藏着什么?”画外音问道,“让我们一起进去探个究竟。”

漫画的最后一页改述了托尔斯泰故事的最后一段。虽然魔鬼利用了伊凡几位哥哥的贪婪与好战,但它们却无法腐蚀伊凡的灵魂,而伊凡的勤劳和慷慨最终为他赢得了一座王国,在那里,只要肯干活,便不会挨饿。倒数第二个画格中写道,“在伊凡的王国里,有一条不成文的法律:那些双手细皮嫩肉、好吃懒做的人,必须吃别人的剩菜剩饭。”

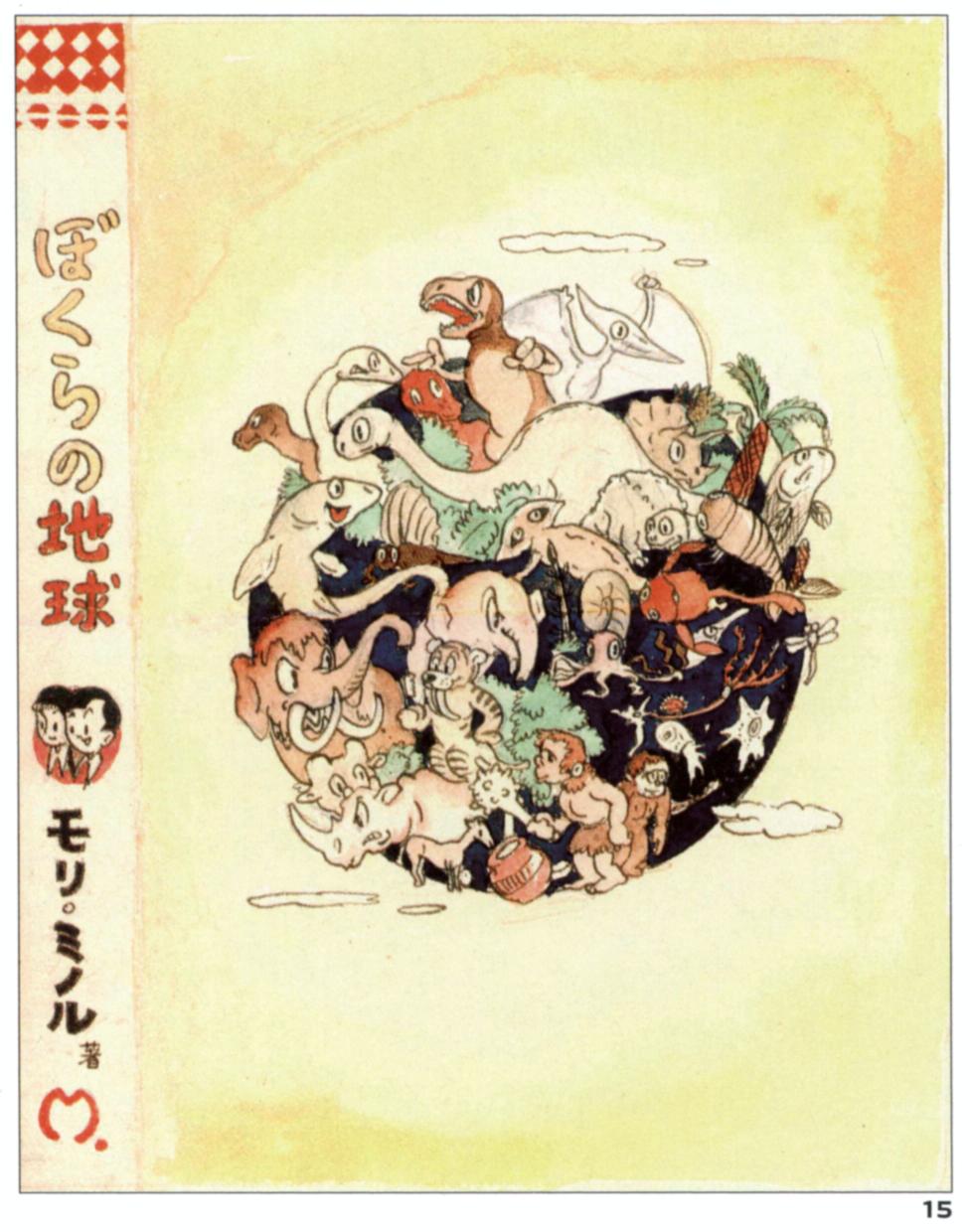

图14, 15. 漫画《我们的地球》(ぼくらの地球)的封面与封底,该作出版于上世纪五十年代。

附录

1. 小松左京在一次访谈中,和克里斯托佛·博尔顿、苏珊·纳皮尔(Susan Napier)、巽孝之、小谷真理和乙部順子谈到了他和其他人的漫画。参见《Science Fiction Studies》(直译为“科幻研究”),第29卷(2002年),页323-339.

Mori Minoru's Day of Resurrection

Tatsumi Takayuki

Christopher Bolton (tr.)

As Japanese science fiction entered the new millennium, its fans might have expected the awakening of elder powers, forces that had long lain dormant. Yet no one foresaw the second coming of Mori Minoru.

A phantom manga artist who published fifty years ago, Mori was the force behind a short-lived but influential series of comics that ceased publication with a puzzling suddenness in the fifties. In the last few years Shogakkan has finally published facsimile editions of this artist’s complete works, which were acknowledged in their day by the likes of Tezuka Osamu, then an up-and-coming artist himself. Matsumoto Leiji (famous in Japan and the West for manga like Star Blazers [Uchu senkan Yamato] and Galaxy Express 999 [Ginga tetsudo 999]) listed Mori, Tezuka, and Tagawa Kikuo as the period’s three great artists.

But despite this acclaim, one day the man who called himself Mori Minoru stopped publishing and all but disappeared. It was almost ten years before he surfaced again, this time as a writer of fiction. In 1961 he entered a science fiction story contest sponsored by Hayakawa’s SF Magazine and won an honorable mention for his story “Pacem in Terris” (“Chi ni wa heiwa o”). The next year he debuted in the same magazine under a new name, with “Memoirs of an Eccentric Time Traveler” (“Ekisentoriki”). And in 1963, “Pacem in Terris” and “The Taste of Green Tea and Rice” (“Ochazuke no aji”) were nominated for the fiftieth Naoki Prize, Japan’s best-known award for fledgling authors of popular fiction. This was the death of the manga artist Mori and simultaneously the birth of the first generation of Japanese science fiction, in the person of one of its great masters, Komatsu Sakyo. Komatsu would go on to help found the genre of prose science fiction in Japan and then help export it to the West with his novel Japan Sinks, which was translated into English, Spanish, Russian, and a half dozen other Western languages.

What summoned Komatsu’s early manga from the dead just a few years ago was the discovery (on the shelves of the manga store Mandarake) of a single copy of his work Subterrocean (Daichiteikai, 1950–52). This prompted Komatsu to search his own archives, where he uncovered the manuscripts for many of the manga he penned in his student days. Hearing of the (re)discovery in the fall of 2001, editors at Shogakkan rushed to reissue the works, and in early 2002 they were published in four volumes as The Complete Phantom Manga of Mori Minoru, a.k.a. Komatsu Sakyo (Maboroshi no Komatsu Sakyo = Mori Minoru manga zenshu). Komatsu had just turned seventy, a time for retrospective publications, and one can hardly imagine a more fitting one. [1]

Komatsu was born Komatsu Minoru, in Osaka in 1931. He attended Kyoto University, graduating in 1954 with a major in Italian literature and a taste for the avant-garde: his thesis was on Luigi Pirandello, and he was an avid reader of experimental Japanese authors like Hanada Kiyoteru and Abe Kobo. In the years after the war much of Japan was struggling economically, and as an impoverished student, Komatsu turned to manga as a source of income. Inspired by the work of Tezuka Osamu, in 1949 he started drawing under the pen name Mori Minoru. He found that manga were easier to sell than prose manuscripts: publishers bought all of his work, and he was soon earning money. After graduation he had a series of other jobs—as a factory manager, a radio comedy (manzai) writer, and a correspondent for the financial magazine Atom—up until his debut as a science fiction author.

In 1964 Komatsu’s novel The Japanese Apache (Nihon Apachezoku) sold over fifty thousand copies. In the same year he published Day of Resurrection (Fukkatsu no hi), which Battle Royal director Fukasaku Kinji filmed in 1980. In 1966 Komatsu wrote At the End of an Endless Stream (Hateshi naki nagare no hate ni), a work that still regularly tops the list in Japanese surveys of the best science fiction of all time. Then in 1973 he published Japan Sinks (Nippon chinbotsu), which described a series of seismic events that submerge the Japanese archipelago. Prefiguring the Tom Clancy simulation genre, it sold four million copies and spawned a 1973 film and (coming full circle) a popular manga series. An abridged version appeared in English in 1976. And interest in the work continues today: in 2006 the talented young director Higuchi Shinji produced a beautiful and radical remake of the 1973 film version.

After winning several Japanese science fiction fan prizes, Komatsu helped inaugurate the Japanese SF Grand Prize in 1980 while serving as the third president of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of Japan (SFWJ; http://www.sfwj.or.jp). And in 2000 Kadokawa Haruki Publishers established an award in his name. He is still writing: Galleries of Emptiness (Kyomu kairo), the novel he calls his life’s work, is in progress.

Rereading Mori Minoru’s manga with Komatsu’s history in mind, we see an almost frightening continuity, a half century of genius. Komatsu’s student leftism sheds light on why Mori choose to illustrate Leo Tolstoy’s masterpiece Ivan the Fool (Iwan no baka, c. 1950). And today we can see the link between works like the manga Andromeda, Terror of the Cosmos (Dai uchu no kyofu Andromeda, 1950s) and Ivan Efremov’s novel The Andromeda Nebula. It was, after all, Komatsu’s admiration for this Russian science fiction writer that spurred him to develop his own theory of science fiction.

But the most striking work is the one that triggered Mori’s return, Subterrocean. Published in 1950 by Fuji Shobo, in 1951 by Hakuchosha, and in 1952 by Mitama Shobo, it changed designs with each move and enjoyed striking popularity. The story develops from the fantastic conceit that the world’s four great deserts—the Gobi, the Sahara, the Arabian Desert, and Iran’s Great Salt Desert—are connected by a vast underground sea, home to a mutant tribe of fish men called the Demones. The plot revolves around a “tectonic manipulator” whose Tesla coil technology can shift the earth’s crust and potentially eradicate this underground pocket of water. From the manga’s point of departure, it is only a short trip to the world of Japan Sinks, where geologic shifts submerge Japan and consign its citizens to a life in diaspora, like the Jewish peoples.

In 1995 the devastating Kobe earthquake hit Komatsu’s own Kansai region, and in the same year the Tokyo subway gas attacks were carried out by the Aum Shinrikyo cult (whose supernatural proselytizing manga series was subsequently the focus of its own subcontroversy). In the wake of the attacks, there were rumors that the cult’s science division had been conducting research on Tesla coils, stemming from their interest in building an earthquake machine of their own. Published in 1950, Subterrocean was set fifty years in the future, but it did not take even that long before it started to come true.

PLATE 1. An opening page from Subterrocean (Daichiteikai, 1950-52). The caption for the street scene tells us, "Our story, like so many other science fiction manga, begins fifty years in the future..." COURTESY KOMATSU SAKYÔ.

PLATES 2, 3, 4, AND 5. Cover and three interior pages from Subterrocean (Daichiteikai, 1950-52). At the top of the middle image, Dr. Bourdeaux explains his "Tectonic Manipulator," which can control the movement of the Earth's crust. Originally designed to prevent earthquakes, these machines have been installed in the world's great deserts as part of an elaborate experiment to depress the surface and raise the underlying strata, to eliminate the vast water pocket that exists beneath these deserts. But this subterrocean is inhabited by a tribe called the Demones...

In one of the concluding frames, an inky figure introduces himself as "the shadow voice — the author," and tells the reader that the story is at an end. "Can you understand how Kishibe Ichirô could come to do such a horrible thing?" it asks. "Was it his sin? His nature? No. What delivered him into the hands of the devil was the miserable society of the time. He was just one of its poor and oppressed. And what can save people like this? Not the gods, but other people and their love. If we are to live as human beings, we must build a more humane world." COURTESY KOMATSU SAKYÔ.

PLATES 6 AND 7. Front and back cover art for Laboratory No.5 (Dai go jikkenshitsu, 1950s). COURTESY KOMATSU SAKYÔ

PLATES 8, 9, AND 10. Cover art and two interior pages from Andromeda, Terror of the Cosmos (Dai uchú no kyôfu Andoromeda, 1950s). In this scene, the villain Dr. Ryuryu self-destructs, leading to the death of the heroine Yurii, who is revealed to be the doctor's creation. "I am a robot controlled by his thoughts," she confesses to the hero. "My electric brain was so finely put together that I started to have feelings. In other words, I became a living being – just like a human."

In the following frames, it is announced that Dr. Ryuryu's gravity device has been destroyed, and the Earth is out of danger. "We have been saved," says the speaker. "The crisis has passed, and peace has returned to the earth. You see, ladies and gentlemen, in the face of a trial unlike any we have ever before faced, the patience, the hard work, and the courage of humanity have prevailed, aided by a love that stirred even a machine." COURTESY KOMATSU SAKYÔ.

PLATES 11, 12, AND 13. Title page and opening and concluding pages from Ivan the Fool (Iwan no baka, c. 1950), based on the short story by Leo Tolstoy. The story opens with the reader standing at the entrance to the Demon's Palace, home of the devils who will tempt Ivan and his brothers. "What lurks behind these doors?" the narration asks. "Let us enter together and find out."

The concluding page of the manga paraphrases the final passage of Tolstoy's story. While the demons have capitalized on the greed and bellicosity of Ivan's brothers, they are unable to corrupt Ivan, whose hard work and generosity earn him a kingdom of his own – a place where no one goes hungry if he or she is willing to work. The final panels read: "In Ivan's kingdom, there is one unwritten law: Those with the lilywhite hands of the leisured must eat the leavings of others." COURTESY KOMATSU SAKYÔ.

PLATES 14 AND 15. Back and front cover art for Our World (Bokura no chikyû, с. 1950). COURTESY KOMATSU SAKYÔ.

Note

1. Komatsu discusses his own and other manga in an interview with Susan Napier, Otobe Junko, and myself, in Science Fiction Studies 29 (2002): 323–39.